For many of the world's great artists, the way their artistry changes throughout their life is part of their greatness. At the same time, both fans and critics can be apprehensive to accept a sharp shift in the image or music of an artist as it breaks the previously established norms or their craft. Andrew Murnane takes a deep dive into some of the mercurial acts from Ireland and Great Britain through the lens of the British band Black Country, New Road.

Very few new artists have burst onto the scene with such an immediately well-defined sound as Black Country, New Road. The British group, led by frontman Isaac Wood, forged their sonic identity with 2021’s For the First Time, blending post-punk with jazz flourishes and themes of alienation. His monotone delivery, full of irony and self-deprecation became immediately synonymous with the group. Then, days before the release of their sophomore album Ants from up There in 2022, Isaac Wood left the band.

Three years on, Forever Howlong. The first studio album post-Wood. Black Country, New Road grapple with new sounds. Songs come shorter, poppier. A new identity. One, remarkably, full of joy and whimsy. This shift points to a broader question: what happens to an artist’s past and present when they change so drastically? And how to evolve without losing one’s identity?

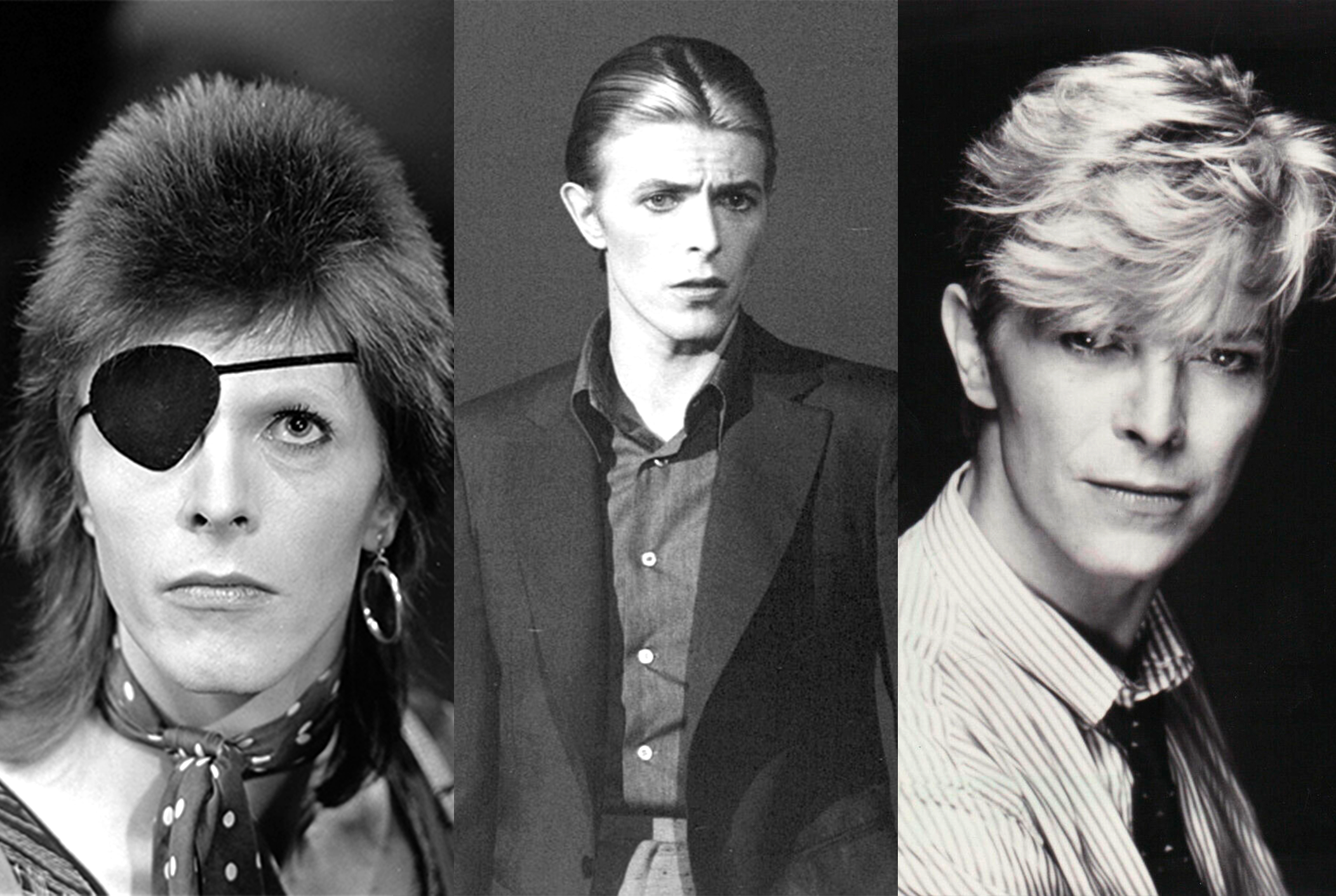

They aren’t the first artists who’ve reinvented themselves. David Bowie moved through various stages and eras across his career, exploring fluid identities and personas. From the sci-fi glam of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane to the moody and contemplative Berlin Trilogy. Bowie has long been regarded as a chameleon. Shapeshifting and fluidity are part and parcel of his identity.

Tom Waits’ evolution was more gradual, occurring piecemeal over subsequent albums. The rough-around-the-edges singer-songwriter pouring his heart out to fellow barflies on 73’s Closing Time is a far cry from whatever it is he’s become over a decade later on Rain Dogs. His influences shifted to the avant-garde and quasi-mythical. Although, with his gravelly voice and tall tales of opium dens and debauched sailors on shore leave, Waits still plays the outsider.

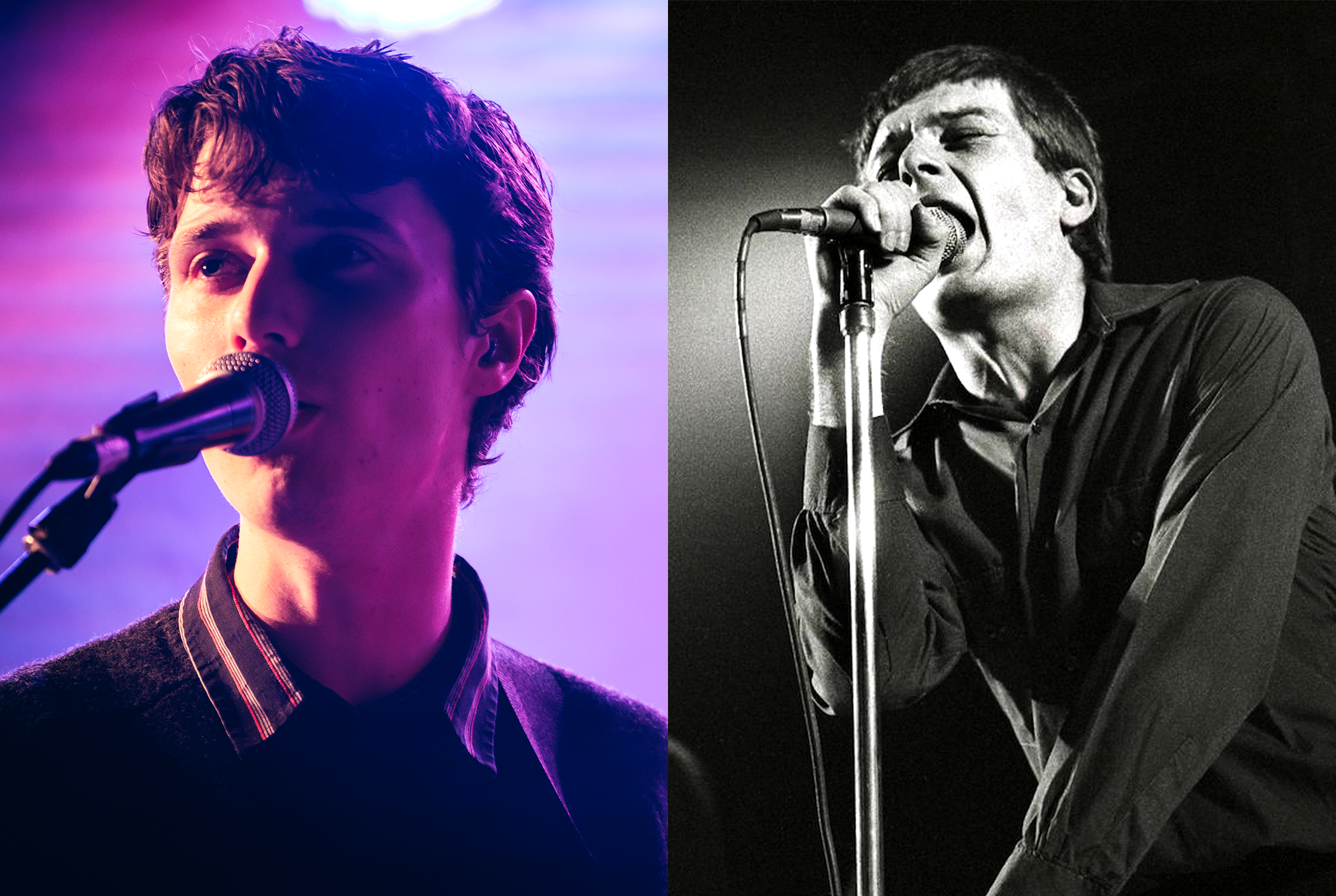

Like Pink Floyd before them and Black Country, New Road after, Joy Division too had to reconsider their musical identity after losing a lead singer. Pink Floyd kept the name but swapped frontmen, with Roger Waters and David Gilmour vying for Syd Barrett’s place. Joy Division changed their identity in a more drastic way after lead singer Ian Curtis died by suicide. They became a different band with a new name and a new genre. New wave: New Order.

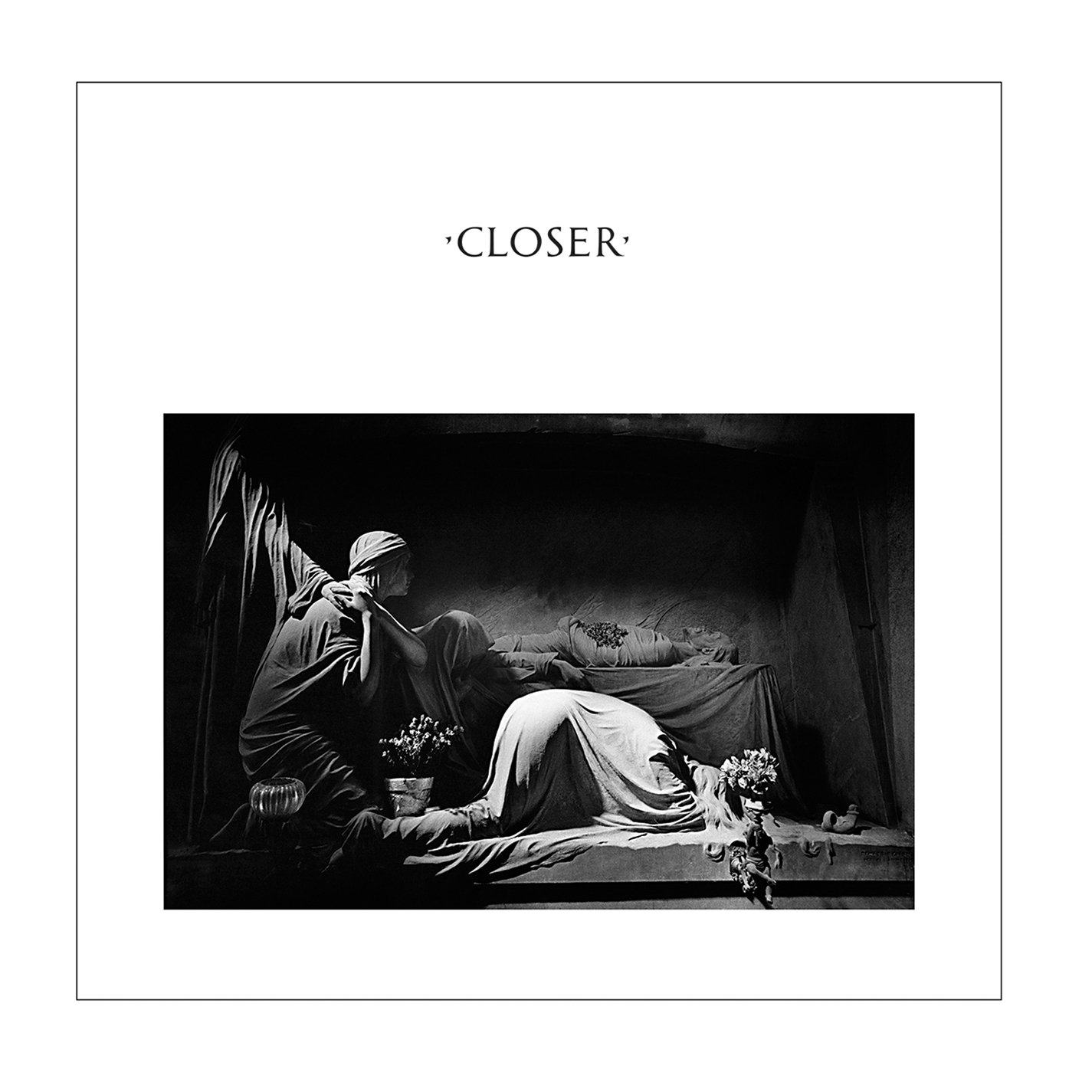

Perhaps becoming New Order was necessary for the band to move forward. After bargaining and depression, the final stage of grief is acceptance. After all, it’s impossible to return to Joy Division’s baroque post-punk without a profound sense of sadness. Nowhere is this more evident than their second album, Closer. The dual meaning of the title – an unfulfilled longing for intimacy; and climactic finality – is made all the more impactful by the cover image: grief and mourning in a stone sculpture. It goes a layer deeper, the sculpture comes from a tomb.

Likewise, it’s now impossible to revisit Ants from up There without scanning for indications of Wood’s unhappiness. Refrains like ‘Ignore this hole I’ve dug again’ take on a new meaning. Wood repeats this plea across multiple songs. His departure was – as far as we know – as much a shock to the band themselves as it was for fans. Yet in these moments he seems to be pre-emptively begging their (and our?) forgiveness.

Of course, no work of art has a single fixed meaning. And there’s a danger of being overly literal, interpreting songwriters’ often complex and conceptual poetry as diaristic. After all, we have no guarantee that Curtis is singing as Curtis on Closer. No more than we can be guaranteed that the version of Wood we meet in on Ants from Up There is the real Wood.

Artists often use personas, metaphors, and indirect ways to explore themes. But context does colour how we respond to music. Greater awareness can deepen our sensibility and our ability to be moved. We can pick up on common threads that resonate across a project. And like with the Appiani tomb on Closer’s album sleeve, our knowledge about the people who made the music we love naturally informs how we respond to it.

With Forever Howlong, expectations for a new release are once again high. How will the group respond to the gaping hole in their line-up? Georgia Ellery (violin, guitar), Tyler Hyde (bass) and May Kershaw (keyboard, accordion) have stepped up to share lead vocals. This marks more than a shift in voices. The new vocal interplay explodes the interiority that marked previous albums. Although a lot of the same bombastic instrumentation is still to be found here, it’s now in service of a different emotional register.

A new lineup brings new artistic sensibilities forward. First single Besties is more upbeat than anything Wood would have brought to the table. Still, between TikTok references and cute nicknames, the lyrics nonetheless disclose a more vulnerable layer. The narrator indicates gently but clearly that her feelings go deeper. The intimate friendship uniting the narrator and her ‘bestie’ renders any romantic catharsis impossible.

Brighter, jauntier sounds only intensify the loneliness – a balance familiar to any New Order fan. One vocalist on Forever Howlong sings ‘I think I’d like to be a little lighter,’ and this goes for the sound of the new era. Where Wood hid his vulnerability behind sunglasses, the new lineup lets in the sunlight. Just look at the album cover. It’s an important statement to keep the name. It casts the band’s development as an evolution, rather than a rupture with its past.

Artists are always evolving. Today, acts like Fontaines DC may retain the same lineup but have totally shifted their style. The stadium-filling international rockstars on Romance are a far cry from the Dublin native post-punks who broke through on Dogrel. On the other hand, Geordie Greep may have lost the bandmates who made up his group Black Midi but – if 2024’s The New Sound is any indication – he’ll be continuing that artistic project as a solo venture. Most Tom Waits fans would rank later period works where his delivery is its most unhinged like Rain Dogs amongst their favourites.

Sometimes we bemoan it, like my own reticence to embrace Fontaines DC in their new aesthetic, but generally we want artists to evolve, move with the times, and push new boundaries. Forever Howlong is the latest chapter in a much longer narrative, one that spans beyond the band themselves. One that proves artist’s identities – however fragile they may appear – are often surprisingly resilient across vast shifts in content and style.