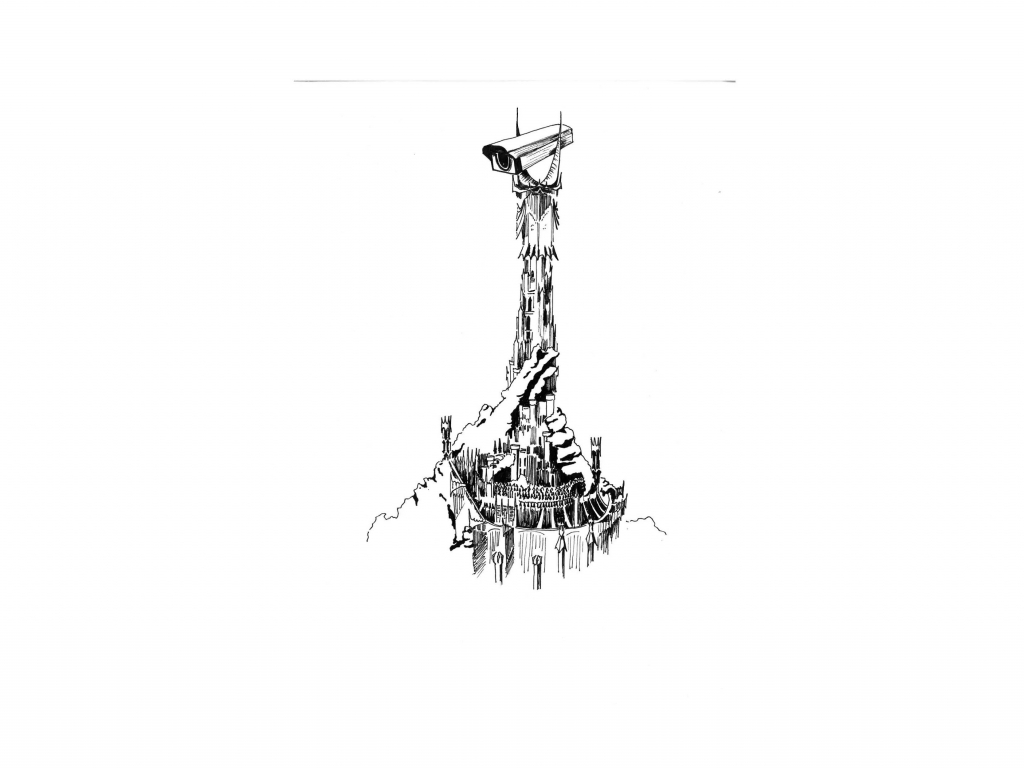

Sweden’s mandatory personal registry – which makes public the address, salary, and personal identity number of every Swedish citizen and resident – is a system that stands at odds with the EU’s stance toward personal information, which is focused on increasing privacy and protections. Lundagård’s Evan Farbstein takes a skeptical look at this Swedish system, and the websites that are profiting from it.

Google my name. After my Lundagård page and some social media profiles, the fifth result is a website which has my Swedish address, turn-by-turn directions to my apartment’s front door (“third floor, second door on the right”), the names of the people I live with, and my birthday. For a fee, you could also access the last 4 digits of my personal identity number and my salary. If you live in Sweden, the same info about you is just as easily attainable. Does that terrify you as much as it terrifies me?

Maybe you’re thinking that so much of your info – your photos, your likes and dislikes, events you’ve attended – is online already, so what’s the big deal? I’d argue the big deal is that you made the decision to put that info out there, while in the case of these Swedish info-sharing sites (there’s a handful of them) you never chose to publish your address. The sites scoop this info from the Swedish Tax Agency, which makes public the birthdays and addresses of every Swedish citizen and resident. It’s not a system you choose to be (or not be) a part of: the Swedish Tax Agency shares this info by default, and the privately-run, for-profit sites publish it without your consent. You can request to remove yourself from the sites (the sites do not have to comply), but you can’t remove yourself from the Tax Agency registry without special permission from the police, which you can’t get unless you can prove that your info being public is a threat to your safety.

On the surface it might seem like agreeing to hide your info if there’s a threat against you solves the safety issue. But let’s say you meet a creepy person at a nightclub on a Friday night. You don’t know right away that they’re creepy – they seem nice enough on the surface – and you add them on Facebook. Your Facebook account has your real name: already, this person has enough info to find your address. Or maybe you exchanged phone numbers, and only used your first name; this person could still find your address using these info-sharing sites. By the time that the creepy person has threatened your safety, they already have more than enough info to stalk you, no matter how quickly the police are able to hide your info when you’re able to contact them Monday morning at 11:00.

Besides the personal safety implications, it seems like giving an identity thief almost all the info they’d need to open a bank account in your name is just too much risk. But don’t worry, one of those info-sharing sites, Ratsit, has you covered: you can buy a service from them to help protect your identity (ostensibly from people who might steal it using their site).

“I respect that there are those who think it is a violation of privacy, but it’s not wrong in the legal sense,” said Ratsit CEO Anders Johansson to SvD, in response to the public outcry his company endured in 2007 when they announced a service that would let you check any Swedish resident’s income.

Johansson agreed to speak to Lundagård for this article. Since in the past he has frequently defended Ratsit’s legality, we asked him if he believed what Ratsit does is not just legal, but ethical.

“Yes, we publish what our elected officials have chosen to be available to the public. It’s a basic principle within [the Swedish] public that society should be fair and transparent,” said Johansson. And Johansson follows these principles himself, leaving all of his own information visible on Ratsit.

Or maybe you exchanged phone numbers, and only used your first name; this person could still find your address using these info-sharing sites. By the time that the creepy person has threatened your safety, they already have more than enough info to stalk you, no matter how quickly the police are able to hide your info when you are able to contact them Monday morning at 11:00.

Sweden’s attitude toward personal privacy is especially surprising when viewed in the context of the EU, which is taking an increasingly active stance toward protecting personal privacy rights, as the recently-enacted GDPR regulations show. And, in an ironic twist, the GDPR requires these Swedish info-sharing sites to ask for permission to use cookies in your web browser. In their privacy policy, Hitta.se even claims: “Our users trust is of the utmost importance to us, and we therefore take responsibility for protecting your privacy” – an odd statement to come from a company whose business model is based on sharing your information without your consent and profiting by advertising to the people who come to see it.

So how is this GDPR compliant? EU member states are allowed exceptions to the GDPR’s restrictions for processing of personal data, if necessary to maintain the right to freedom of expression in their country. Sweden’s public registry falls under that allowance, and the websites that share this information have a publishing authorization that supersedes the GDPR.

The Swedes I’ve asked about this say that their relationship to their government and their fellow citizens is based on trust. But trustworthy systems are only trustworthy until they’re not anymore. What if the cultural or political landscape in Sweden changes? (It’s not like that’s unprecedented in Europe.) Isn’t it better to be overly cautious than naive – better to be safe than sorry?

Let’s take a best case/worst case scenario look at this. What’s the best-case of someone needing to know my apartment, roommates, and birthday? They’re planning a surprise party for me and want to get my roommates in on it. What’s the worst case? They hate me, and they want to come to my apartment to kill me, and, just to drive the point home, they want to kill my roommates as well, and they want to do it on my birthday.

I know that that’s not a likely scenario – and, as one Swede I shared it with bluntly stated, may be an example of middle-class American paranoia. In my defense, I wouldn’t say I’m expecting this to happen. I’m just asking questions. I believe it’s healthy to exercise skepticism toward people and institutions that have power over me. And, for the sake of skepticism, I ask Sweden to consider the benefits of this system versus the risks that come with it. It’s convenient to be able to look up where your friend lives, or quickly find your parent’s birthday, or see what your coworker earns when you’re trying to negotiate a raise. But is that convenience really worth enabling stalkers and forfeiting your right to privacy?

Maybe growing up in America, a country where a citizen’s relationship to their government is defined by skepticism, means I won’t ever understand why Sweden tolerates something that feels to me like a gross breach of privacy. But I’d like to try to understand. If you want to help me do so, please leave a comment – or, you know, just knock on my front door.